ANJC’s newest program aims to keep Alaska Native youth out of the juvenile justice system

Four years ago, when she became the Director of Operations at the Alaska Native Justice Center (ANJC), Tammy Ashley had a dream. She wanted to rebuild ANJC’s youth programs — starting with forging a relationship with McLaughlin Youth Center (MYC).

“Alaska Native teens are disproportionately taken into the custody of the juvenile justice system,” Tammy said. “They’re cut off from their cultural, community, and family connections, which leads to a cycle of recidivism and institutionalization. Our goal is to reach young people involved with the juvenile justice system and help them develop the networks of support that will prevent them from needing our services down the road.”

Thanks to funding from the Administration of Native Americans, ANJC has partnered with the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) to create ANJC’s Duhdeldih Youth Transition Support program. Through Duhdeldih (“we are learning”), ANJC staff have begun providing culturally-informed programs for young offenders at MYC.

Learning Together

Located in Anchorage, MYC is only one of four DJJ facilities that provide long-term secure treatment services; it is the only facility that provides long-term treatment for female teens. This means that many of the youth living in at MYC were removed from communities elsewhere in Alaska.

Duhdeldih staff are focused on building up the protective factors among both rural and urban Alaska Native youth whose adolescence has been disrupted by removal from family, by institutionalization, and by juvenile justice system involvement.

“Working with youth reentering society after institutionalization, it’s different than working with adults,” pointed out ANJC Youth Program Manager Justin Hatton. “They’re still seeking guidance, they’re still learning. What we do is to help them better understand themselves and connect them with their community and culture.”

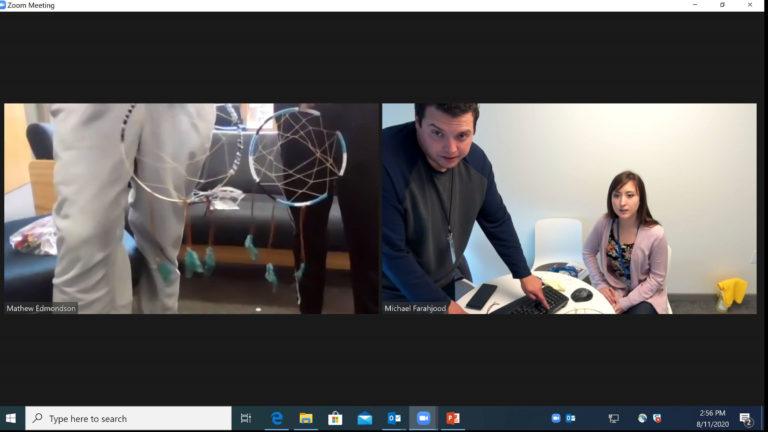

ANJC Youth Advocated Michael Farahjood leads MYC youth through activities and discussions centered around topics like culture, coping skills, mental health, building relationships, and other concepts that help young people build the networks of support necessary to keep them out of the system once they’re released.

“So many of these kids don’t have that role model who can act as a guide and a resource,” said Michael. He uses the story of his own difficult adolescence to connect with MYC youth. “I can give them all the tools I think will help them, but without that connection, it’s not going to do anything. It’s really all about building those relationships.”

Setting the Stage for Success

ANJC’s relationship with youth doesn’t stop within the walls of MYC, though. Part of Duhdeldih’s mission is to provide supportive services to young people, especially as they get ready to leave any youth detention or inpatient behavioral facility. Michael and other youth advocates tap into ANJC’s array of services, as well as CITC’s youth, recovery, and family support programs, to ensure that teens exiting MYC and other youth facilities find the assistance they need to avoid recidivism.

“Our job is to set the stage for Alaska Native youth to be successful, stay out of the justice system, and do anything they want in life,” Justin said.

Supportive services may include anything from access to educational opportunities and internships, to support for recovery from addiction, to rental or other assistance for teens and their families. For instance, one young man Michael worked with landed an interview for CITC’s Youth Employment Program Internship, so ANJC helped him get a cell phone to take calls from potential employers and supplied him with a bus pass to get to his interview.

“It’s really about developing a relationship and understanding where they’re at, seeing what their needs are,” Michael said.

“What we do is walk alongside them, give them options, write down goals,” Justin added. “Then we work on how do we get to those goals? We give them the voice to drive process. But we’ll be their co-pilot. If they’re about to crash, we’re there to pick them back up and redirect.”

Coping with COVID

Almost as soon as ANJC staff launched the program, though, COVID-19 cut off their on-site access to MYC. ANJC quickly pivoted to virtual delivery of programs and services that engage MYC youth with cultural activities.

Youth advocates communicate with interested MYC residents through Zoom to inform them about program eligibility and resources ANJC can offer. Meanwhile, staff have designed presentations and interactive games to help young people talk about ideas like connectedness, having a healthy adult in their lives, and decision-making.

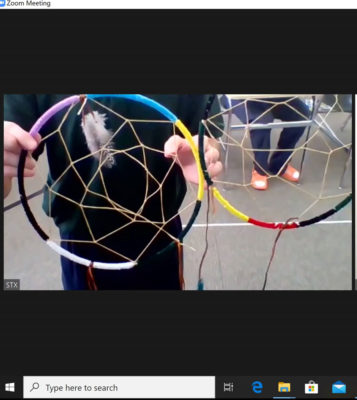

This fall, Duhdeldih staff created culture kits with all the materials and tools youth needed to create items like dreamcatchers. They Zoomed into MYC and instructed participating youth over video, while onsite staff from MYC assisted the teens in person.

“It’s been a wonderful relationship with MYC staff,” said Justin. “Despite the obstacles we’ve gone through with COVID, there was a real attitude of ‘we can do this!’ And now we are.”

Whether it’s delivered virtually or in person, Duhdeldih is addressing the unmet needs of Alaska Native youth and working to create an Alaska where Native teens are no longer taken into the juvenile justice system in disproportionate numbers.