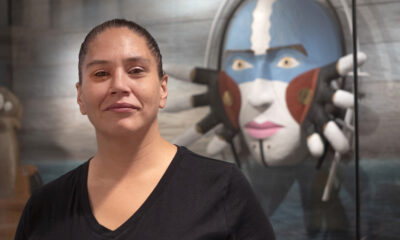

Alaska Native people face long odds in the justice system—but with the help of ANJC, Toni Sanderson beat the statistics

Toni Sanderson isn’t a statistic. But her experience is reflected in numbers that tell the story of an imbalance of justice in Alaska.

Numbers like: 35. That’s the percentage of Anchorage’s Alaska Native population that has witnessed domestic violence. [1]

Toni grew up in Hydaburg, in southeast Alaska, where she saw her own share of violence in the home. “My mom suffered from alcoholism, and she lived a party lifestyle,” Toni recalled. “I grew up watching my mom be physically abused, and I was sexually abused at a young age, too.”

When she lost her mother to suicide, Toni didn’t know how to cope. She tried cutting, considered suicide herself—and then, like her mother, she turned to substance abuse.

Getting Out and Getting Help

“I was a drug user for six years,” Toni said, “and I needed to supply my addiction. So I stole from people, I lied to them, I cheated. I ended up in prison, with a lot of regrets.”

In prison, Toni decided she wanted to make a change. But when she was released, she faced another significant number: For 62 percent of people who serve time for a felony, their release begins a countdown to the day they return to prison [2]. Alaska Native people, in particular, face staggering odds: They have higher rates of re-arrest and reconviction than offenders of any other ethnicity in Alaska [3].

Toni was well aware that in order to stay out of prison, she needed support. She started by entering transitional housing at the House of Transformation. There, she heard about an organization that specializes in providing Alaska Native people with substance abuse disorders who are transitioning out of prison: the Alaska Native Justice Center (ANJC).

Safety Net

Numbers matter at ANJC, too. For instance: 12 months. That’s when the highest recidivism rates occur—the period of time when someone released from incarceration is most likely to reoffend and go back to prison [4].

The reason often boils down to a lack of support. The things the general public sometimes take for granted—access to education and stable housing, a secure job, a social safety net, even basic identification—are often difficult or nearly impossible for previously incarcerated people to obtain.

ANJC helps people stay out of the corrections system by providing comprehensive, culturally informed support services, including financial support, housing or rental assistance, employment, transportation, and support groups. Every year, ANJC helps about 500 individual successfully reenter the community following incarceration.

Toni is one of those individuals. ANJC Case Worker Kuuipo Miramontes worked with her to secure employment. Then, when a false positive on a drug test sent Toni back to prison, Kuuipo advocated for Toni to keep her job.

“She went to bat for me,” Toni said. Kuuipo also got Toni bus passes for transportation, took her shopping for work clothes, and provided rental assistance.

Escaping a Different Prison

Getting and keeping a job wouldn’t have been possible, though, if Toni hadn’t dedicated herself to recovery. Although she had engaged with recovery programs before, she said, “I wasn’t ready then. This time, I was ready to escape from my own mental and emotional prison.”

She joined ANJC’s Moral Reconation Therapy (MRT) group, a peer-driven support group that equips participants with better decision-making and reasoning skills by helping them focus on the moral aspects of their past substance-abuse illnesses and behaviors. MRT group participants also complete 20 community service hours.

“When I was fresh out of prison, ANJC and the MRT program gave me the necessary tolls I needed to get my life back together,” Toni said.

“Not the Same Toni as Before”

Today, numbers tell a different story about Toni’s life. Like 19: That’s how many months she’s been sober. Or 3/22: That’s the month she earned her Peer Support certificate, which equips her to act as a mentor to others in recovery.

Or 15: the age of Toni’s son, who lives with her aunt and uncle in Hydaburg. “He’s safe and well taken care of, and I get to be part of his life again,” Toni said.

She’s holding down a job as a kitchen manager for Denny’s. One day, she would like to be a youth drug and alcohol counselor; she hopes for the chance to help a young person before they get on the wrong path.

“That’s why I want to share my story—in hopes that it inspires somebody to change their life,” she said. “Two years ago, I was digging my way out of a grave, begging God to just please take me. But I’m not the same Toni I was before. I’m never going to be that Toni again. The Alaska Native Justice Center saved my life. It showed me how to love myself again.”

You can help people like Toni make real change in their lives. Be a voice for justice: Donate to ANJC’s Voices for Justice fundraising campaign today.

—-

[1] Alaska 2013-2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey, Div. Public Health, Section of Chronic Disease Prevention

[2] Alaska Criminal Justice Commission (ACJC). (10/28/2021) Annual Report 2021 p. 31

[3] Alaska Judicial Council. (November 2011). Criminal Recidivism in Alaska, pp 53-54.

[4] AJC. (November 2011). Criminal Recidivism in Alaska, 2008 and 2009, pp. 15-16.

See more of Toni’s story and other ANJC impact here.